*Winner of the 2015 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Memoir and the 2015 Maine Literary Award for Memoir.

A vivid account of Blanco’s coming of age as the child of Cuban immigrants and his effort to contend with his burgeoning artistic and sexual identities. This book evokes the complexities and glories—and humor—of navigating his two imaginary worlds: the Cuba of the 1950s that his family longed for and his own idealized America.

A poignant, hilarious, and inspiring memoir from the first Latino and openly gay inaugural poet, which explores his coming-of-age as the child of Cuban immigrants and his attempts to understand his place in America while grappling with his burgeoning artistic and sexual identities.

Richard Blanco’s childhood and adolescence were experienced between two imaginary worlds: his parents’ nostalgic world of 1950s Cuba and his imagined America, the country he saw on reruns of The Brady Bunch and Leave it to Beaver—an “exotic” life he yearned for as much as he yearned to see “la patria.”

Navigating these worlds eventually led Blanco to question his cultural identity through words; in turn, his vision as a writer—as an artist—prompted the courage to accept himself as a gay man. In this moving, contemplative memoir, the 2013 inaugural poet traces his poignant, often hilarious, and quintessentially American coming-of-age and the people who influenced him.

A prismatic and lyrical narrative rich with the colors, sounds, smells, and textures of Miami, Richard Blanco’s personal narrative is a resonant account of how he discovered his authentic self and ultimately, a deeper understanding of what it means to be American. His is a singular yet universal story that beautifully illuminates the experience of “becoming;” how we are shaped by experiences, memories, and our complex stories: the humor, love, yearning, and tenderness that define a life.

Read Excerpts

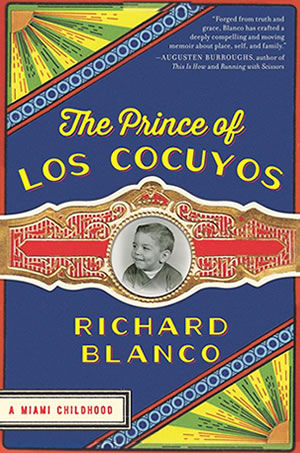

The Prince of Los Cocuyos

When we moved to Miami, Abuela became a bookie for La bolita, an illegal numbers racket run by Cuban mafiosos. She took bets all day long, recording them on a yellow legal pad and calling them in every night to Joaquin, the big boss. She also sold Puerto Rican lotto tickets, which she marked up twenty cents. Every month Graciela, her contact in San Juan, would send a stack of tickets; in exchange, Abuela split the profits with her: 25 percent for Graciela, 75 percent for herself. On Saturday nights, I’d help Abuela with her bookkeeping for the week. We’d set up at the kitchen table, her disproportionately large bust jutting out and over the tabletop and her short legs that didn’t reach the floor swinging back and forth underneath the chair. “Make sure all the pesos are facing up—and all the same way,” she instructed every time we’d begin sorting the various denominations into neat stacks.

As we handled the bills I tried teaching her about the father of our country, the Gettysburg Address, the Civil War, and the other bits of American history I was learning in school. Who’s this? What did he do? I’d quiz her, pointing at the portrait of Jackson, his wavy hairdo and bushy eyebrows, on a twenty; or at Lincoln’s narrow nose and deep-set eyes on a five. But it was useless: “Ay, mi’jo, they’re all americanos feos. I don’t care who they are, only what they can buy,” she’d quip, thumbing through the bills, her fingernails always self-manicured but never painted. Without losing count, she’d quiz me on la charada―a traditional system of numbers paired with symbols used for divination and placing bets. She’d call out a number at random, and I’d answer with the corresponding symbol she had me memorize: número 36―bodega; número 8―tigre; número 46―chino (which I always forgot); número 17―luna (my favorite one); número 93―revolución, the reason why I was born in número 44―España instead of in número 92―Cuba. Everything in the world seemed to have a number, even me: número 13―niño.

In a composition book with penciled-in rows and columns, she’d tally her profits, down to the nickels and dimes I helped her wrap into paper rolls. Sometimes―if I begged long enough―she let me keep the leftover coins that weren’t enough to complete a new roll. It seemed like a fortune to me at age nine, enough to buy all the Bazooka bubble gum I wanted from the ice cream man once a week; even enough to buy TV time from my older brother, Caco, so I could watch old TV shows like The Brady Bunch instead of football.

Once Abuela and I were done with our accounting, I followed her through the house as she stashed the money in her guaquita, her code name for the hiding places she shared with only me. Ones, fives, and tens went into a manila envelope taped behind the toilet tank; twenties and fifties underneath a corner of the wall-to-wall carpeting in her bedroom. The coin rolls we hid in the pantry, buried in empty canisters of sugar and coffee. “In Cuba I had to hide my pesos from la milicia―those hijos de puta! That’s when I started making guaquita. I even had to hide my underwear from them,” she’d claim. The pennies she tossed into an empty margarine tub she kept at the foot of her blessed San Lazaro statuette in her bedroom. Every Sunday morning she emptied the tub into a paper bag and dropped the pennies into the poor box at St. Brendan’s before mass. “You have to give a little to get a little, that’s how it works, mi’jo,” she’d profess, making the sign of the cross.

Watch Video

Reading at the Miami Book Fair

Praise & Reviews

“Blanco has a natural, unforced style that allows his characters’ vibrancy and humor to shine through.”

– Publishers Weekly (Starred Review)

“The Prince of Los Cocuyos had me laughing time and again with its warm, sweetly self-deprecating portrait of an immigrant family attempting to straddle Cuban traditions and American trends. Richard Blanco describes episodes of cultural mistranslation as funny as “I Love Lucy” reruns. He has sustained a bulls-eye ability to recognize people’s underlying nature, a kind of innocence that most of us lose as we grow up—except those who, like Blanco, grow up to become poets.

– Andrew Solomon, author of Far From the Tree

“Walking into Blanco´s memoir is as familiar as walking into my own home. Who knew it would be so familiar? Are we related? Do we have the same crazy relatives? Maybe the lives of all artists are like this, and just maybe when we recognize our colleagues as ourselves, we have come home, finally, to our spiritual family. Thank you, Richard, for this. The Prince of los Cocuyos is revelation and homecoming.

– Sandra Cisneros, author of The House on Mango Street

“I adored every minute spent with young ‘Riqui’ and his endearing extended family. And at the end⏤an ending so beautiful and throat-catching⏤I felt wonderfully drenched in love.

– Monica Wood, author of When We Were the Kennedys

“In this vibrant memoir, Obama-inaugural poet Richard Blanco tenderly, exhilaratingly chronicles his Miami childhood amid a colorful, if suffocating, family of Cuban exiles, as well as his quest to find his artistic voice and the courage to accept himself as a gay man.”

– O, The Oprah Magazine

“A warm, emotionally intimate memoir.”

– Kirkus Reviews

“Thank you, Richard, for this. The Prince of los Cocuyos is revelation and homecoming.”

– Sandra Cisneros, author of House on Mango Street

“[The Prince of los Cocuyos] includes portraits and scenes, intimately and lovingly rendered… Having honored our nation as a whole in verse, he honors it again, but this time as witness to the life and fortune of one exceptionally American family.”

– Los Angeles Review of Books

“… the anecdotes Blanco shares – such as trying to convince his grandmother to go shopping at the Winn-Dixie supermarket she so feared – are muy cubano and will give readers a sense of Cuban family spirit.

– TheGuardian.com

“In Richard Blanco’s Miami, memories linger outside coffee windows and in Cuban grocery store aisles… In a series of loosely intertwined stories, Blanco describes a childhood marked by loss, humor and hints of an exotic land called America.”

– Associated Press

“[A] sensual new memoir… Blanco’s ear for poetry comes to light in the memoir’s full-bodied language and knack for description… [evoking] the flavors, fabrics and smells of rundown South Beach hotels, all-night pig roasts, disco-era Quinces debuts.”

– Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Forged from truth and grace, Blanco has crafted a deeply compelling and moving memoir about place, self and family.”

– Augusten Burroughs, author of This Is How and Running With Scissors

“The Prince of Los Cocuyos is equal parts touching, heart-ache-inducing, and laugh-out-loud funny.”

– The Daily Beast

“Like many a great bildungsroman, The Prince of Los Cocuyos … portrays a character who feels torn between several different worlds. . . . His search for identity, belonging, and home is one that any reader, regardless of sexual orientation or ancestry, is one that anyone can identify with.”

– The Advocate

“Richard Blanco takes us on a thought-provoking, often hilarious ride in … his coming-of-age memoir. The Cuban and Spanish intellectual, who was the first Latino, openly gay man and immigrant to be commissioned a presidential inaugural poet, illustrates the story of his childhood in the 1970s.”

– Latina Magazine

“I adored every minute spent with young ‘Riqui’ and his endearing extended family. And at the end-an ending so beautiful and throat-catching-I felt wonderfully drenched in love.”

– Monica Wood, author of When We Were the Kennedys

“The Prince of Los Cocuyos had me laughing time and again with its warm, sweetly self-deprecating portrait of an immigrant family attempting to straddle Cuban traditions and American trends.”

– Andrew Solomon, author of Far From the Tree

“A work that is incredibly poignant at one moment, yet hysterically funny with the turn of the page.”

– Huffington Post

“Filled with colorful characters, often poignant and sometimes melancholy, Blanco’s episodic memoir is a meditation on belonging, on self-acceptance, and on his family’s almost mystical connection to Cuba.”

– Booklist

“Blanco’s touching reminiscence has a deep emotional truth. . . . [An] alternately hilarious and moving new memoir.”

– Bookpage

“… this memoir is an exceptional introduction to the writer and his capabilities. The Prince of los Cocuyos embodies the best of his poetic style, in particular his eye for detail and ability to put the reader right in the place where he is.”

– Orlando Weekly