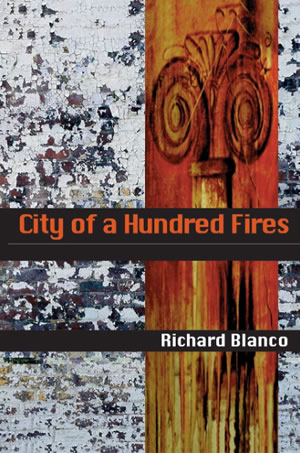

Blanco’s first book and the recipient of the acclaimed Agnes Starrett Poetry Prize, City of a Hundred Fires explores the yearnings and negotiation of cultural identity as a Cuban-American.

Winner of the 1997 Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize. City of a Hundred Fires presents us with a journey through the cultural coming of age experiences of the hyphenated Cuban-American. This distinct group, known as generation ñ (as coined by Bill Teck), are the bilingual children of Cuban exiles nourished by two cultural currents: the fragmented traditions and transferred nostalgia of their parents’ Caribbean homeland and the very real and present America where they grew up and live.

City of a Hundred Fires takes its title from a literal translation of “Cienfuegos,” the city on the southern coast of Cuba where my parents and family are from. I always describe this book as a cultural coming of age “story,” tracing the cultural yearnings and negotiation of growing up Cuban American. The collection is divided into two parts, which I like to think of as “BC” (meaning before Cuba) and “AC” (meaning after Cuba). The “BC” poems are centered around my childhood and young adult life in Miami and the growth of my awareness and identity with my Cuban heritage and history. The “AC” poems chronicle my travels to Cuba seeking and (re)claiming my mythic homeland, where I encountered for the first time the landscapes, places, and family that since my birth were merely hand-me-down stories and black-and-white photos.

Read Excerpts

América

My Cuban family never “got” Thanksgiving. It was one of those traditions without translation. For Cubans, pork isn’t the “other white meat,” it is the “ONLY white meat.” This poem originates from one of my earliest memories of the clash between the two cultures that shaped me.

I.

Although Tía Miriam boasted she discovered

at least half-a-dozen uses for peanut butter—

topping for guava shells in syrup,

butter substitute for Cuban toast,

hair conditioner and relaxer—

Mamá never knew what to make

of the monthly five-pound jars

handed out by the immigration department

until my friend, Jeff, mentioned jelly.

II.

There was always pork though,

for every birthday and wedding,

whole ones on Christmas and New Year’s Eve,

even on Thanksgiving Day—pork,

fried, broiled or crispy skin roasted—

as well as cauldrons of black beans,

fried plantain chips and yuca con mojito.

These items required a special visit

to Antonio’s mercado on the corner of 8th Street

where men in guayaberas stood in senate

blaming Kennedy for everything—“¡Ese hijo de puta!”

the bile of Cuban coffee and cigar residue

filling the creases of their wrinkled lips;

clinging to one another’s lies of lost wealth,

ashamed and empty as hollow trees.

III.

By seven I had grown suspicious—we were still here.

Overheard conversations about returning

to Cuba had grown wistful and less frequent.

I spoke English; my parents didn’t.

We didn’t live in a two-story house

with a maid or a wood-panel station wagon

nor vacation camping in Colorado.

None of the girls in our family had hair of gold;

none of my brothers or cousins

were named Greg, Peter, or Marcia;

we were not the Brady Bunch.

None of the black and white characters

on Donna Reed or on the Dick Van Dyke Show

were named Guadalupe, Lázaro, or Mercedes.

Patty Duke’s family wasn’t like us either—

they didn’t have pork on Thanksgiving,

they ate turkey with cranberry sauce;

they didn’t have yuca, they had yams

like the dittos of Pilgrims I colored in class.

IV.

A week before Thanksgiving

I explained to my abuelita

about the Indians and the Mayflower,

how Lincoln set the slaves free;

I explained to my parents about

the purple mountain’s majesty,

“one if by land, two if by sea”

the cherry tree, the tea party,

the amber waves of grain,

the “masses yearning to be free”

liberty and justice for all, until

finally they agreed:

this Thanksgiving we would have turkey,

as well as pork.

V.

Abuelita prepared the poor fowl

as if committing an act of treason,

faking her enthusiasm for my sake.

Mamá set a frozen pumpkin pie in the oven

and prepared candied yams following instructions

I translated from the marshmallow bag.

The table was arrayed with gladiolus,

the plattered turkey loomed at the center

on plastic silver from Woolworths.

Everyone sat in green velvet chairs

we had upholstered with clear vinyl,

except Tío Carlos and Toti, seated

in the folding chairs from the Salvation Army.

I uttered a bilingual blessing

and the turkey was passed around

like a game of Russian roulette.

“DRY,” Tío Berto complained, and proceeded

to drown the lean slices with pork fat drippings

and cranberry jelly— “esa mierda roja,” he called it.

Faces fell when Mamá presented her ochre pie—

pumpkin was a home remedy for ulcers, not a dessert.

Tía María made three rounds of Cuban coffee

then abuelo and Pepe cleared the living room furniture,

put on a Celia Cruz LP and the entire family

began to merengue over the linoleum of our apartment,

sweating rum and coffee until they remembered—

it was 1976 and 46 degrees—

in América.

Mango No. 61

Pescado grande was number 14, while pescado chico, was number 12; dinero, money, was number 10. This was la charada, the sacred and obsessive numerology my abuela used to predict lottery numbers or winning trifectas at the dog track. The grocery stores and pawn shops on Flagler street handed out complementary wallet-size cards printed with the entire charada, numbers 1 through 100: number 70 was coco, number 89 was melón and number 61 was mango. Mango was Mrs. Pike, the last americana on the block with the best mango tree in the neighborhood. Mamá would coerce her in granting us picking rights–after all, los americanos don’t eat mango, she’d reason. Mango was fruit wrapped in brown paper bags, hidden like ripening secrets in the kitchen oven. Mango was the perfect house warming gift and a marmalade dessert with thick slices of cream cheese at birthday dinners and Thanksgiving. Mangos, watching like amber cat’s eyes. Mangos, perfectly still in their speckled maroon shells like giant unhatched eggs. Number 48 was cucaracha, number 36 was bodega, but mango was my uncle’s bodega, where everyone spoke only loud Spanish, the precious gold fruit towering in tres-por-un-peso pyramids. Mango was mango shakes made with milk, sugar and a pinch of salt–my grandfather’s treat at the 8th street market after baseball practice. Number 60 was sol, number 18 was palma, but mango was my father and I under the largest shade tree at the edges of Tamiami park. Mango was abuela and I hunched over the counter covered with the Spanish newspaper, devouring the dissected flesh of the fruit slithering like molten gold through our fingers, the nectar cascading from our binging chins, abuela consumed in her rapture and convinced that I absolutely loved mangos. Those messy mangos. Number 79 was cubano–us, and number 93 was revolución, though I always thought it should be 58, the actual year of the revolution–the reason why, I’m told, we live so obsessively and nostalgically eating number 61’s, mangos, here in number 87, América.

Mother Picking Produce

I trace my love and longing for Cuba to my mother who left behind every last one of her relatives, including seven brothers and sisters, to follow my father to America. This poem attempts to capture a very subtle yet powerful moment when I connected with my mother, not as a parent, but as a woman; the first time I came to understand the fullness of her humanity: the breadth of her loss and pain, as well as her incredible strength and perseverance.

She scratches the oranges then smells the peel,

presses an avocado just enough to judge its ripeness,

polishes the McIntoshes searching for bruises.

She selects with hands that have thickened, fingers

that have swollen with history around the white gold

of a wedding ring she now wears as a widow.

Unlike the archived photos of young, slender digits

captive around black and white orange blossoms,

her spotted hands now reaching into the colors.

I see all the folklore of her childhood, the fields,

the fruit she once picked from the very tree,

the wiry roots she pulled out of the very ground.

And now, among the collapsed boxes of yucca,

through crumbling pyramids of golden mangos,

she moves with the same instinct and skill.

This is how she survives death and her son,

on these humble duties that will never change,

on those habits of living which keep a life a life.

She holds up red grapes to ask me what I think,

and what I think is this, a new poem about her—

the grapes look like dusty rubies in her hands,

what I say is this: they look sweet, very sweet.

Varadero en Alba

According to my parents, Miami Beach was a filthy, ugly beach. There was no beach in the world that could even compare to their beautiful Varadero in Cuba. I never believed their nostalgic chatter, until I saw Varadero for the first time during my first visit to Cuba. This poem is about my encounter with that landscape at sunrise and memories of my father. The stanzas in Spanish were written first, then the English stanzas, which are a kind of response echoing similar images, but are not direct translations. They are reflections of each other, responses of how my two “halves”–the Spanish and English–experienced Varadero.

i. ven

tus olas roncas murmuran entre ellas

las luciérnagas se han cansado

las gaviotas esperan como ansiosas reinas

We gypsy through the island’s north ridge

ripe with villages cradled in cane and palms,

the raw harmony of fireflies circling about

amber faces like dewed fruit in the dawn;

the sun belongs here, it returns like a soldier

loyal to the land, the leaves turn to its victory,

a palomino rustles its mane in blooming light.

I have no other vision of this tapestry.

ii. ven

tus palmas viudas quieren su danzón

y las nubes se mueven inquietas como gitanas,

adivina la magia encerrada del caracol

The morning pallor blurs these lines:

horizon with shore, mountain with road;

the shells conceal their chalky magic,

the dunes’ shadows lengthen and grow;

I too belong here, sun, and my father

who always spoke paradise of the same sand

I now impress barefoot on a shore I’ve known

only as a voice held like water in my hands.

iii. ven

las estrellas parpadeantes tienen sueño

en la arena, he grabado tu nombre,

en la orilla, he clavado mi remo

There are names chiseled in the ivory sand,

striped fish that slip through my fingers

like wet and cool ghosts among the coral,

a warm rising light, a vertigo that lingers;

I wade in the salt and time waves,

facing the losses I must understand,

staked oars crucifixed on the shore.

Why are we nothing without this land?

Praise & Reviews

“Richard Blanco’s City of a Hundred Fires lights up the American literary scene with a fresh new vigor and voice that takes its place at the front rank of poetry… entrancing a wide audience with the music of its language, its beautiful evocation of loss, love and hope.

– Dan Wakefield, American novelist, journalist and screenwriter

“What a delicia these poems are, sad, tender, and filled with longing. Like an old photograph, a saint’s statue worn away by the devout, a bolero on the radio on a night full of rain. Me emocionan. There is no other way to say it. They emotion me.

– Sandra Cisneros, American novelist

“City of a Hundred Fires is one of the most exciting first books of the decade–vibrant and diverse, infused with energy and formal dexterity, equally at ease in Spanish and English…a testimony to the dualities of identity central not only to Cuban but to all “hyphenated Americans” — exile and citizen, emigrant and immigrant, elegist and celebrant. Richard Blanco is a poet of remarkable talents — in any language.

– Campbell McGrath, American poet

“In a keenly impressive debut, Blanco, a Cuban raised in the United States, records his threefold burdens: learning and adapting to American culture, translating for family and friends, and maintaining his own roots. These tensions are punctuated by the number of untranslated Spanish words speckled throughout. Blanco is already a mature, seasoned writer, and his powers of description and determination to get every nuance correct are evident from the first poem. Throughout the first half of the book, Blanco describes the culture of cafe and loss: ‘this place I call home.’ Then, in a delicate stroke, the poems in Part 2 gently switch cultures–from Cubans in the United States to the traveler in Cuba. This collection was awarded the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize; one hopes it will be the start of many such prizes and honors. Absolutely essential for all libraries.

– Rochelle Ratner, formerly with “Soho Weekly News,” New York, Library Journal

“The poet’s nostalgia for Cuba, a life seen through the lens of his parents’ exile, here meets head on his own coming of age in a culturally and racially diverse Miami. Full of vivid and specific detail, dotted with Spanish phrases, these poems arrest the reader much as the Ancient Mariner did, transfixing the listener.

– Maxine Kumin

“Blanco is a fine young poet, and this poetry, the bread and wine of our language of exile, is pure delight, written with Lorca’s El Duende’s eyes and heart. May he continue to produce such a heavenly mix of rhythm and image–these poems are more than gems, they are the truth, not only about the Cuban-American experience, but of our collective experience in the United States, a beautiful land of gypsies.

– Virgil Suarez

“In this remarkable first book Richard Blanco speaks in a wise, compassionate voice that finds beauty in loss and takes bright lessons from despair. These are poems that hurt and heal.

– Gustavo Perez Firmat

“As one of the newer voices in Cuban-American poetry, Blanco writes about the reality of an uprooted culture and how the poet binds the farthest regions of the world together through language. This book describes the price of exile and extends beyond the shores of America and the imagined shores of home.”

– The Bloombury Review