*Winner of the Beyond Margins Award from the PEN / American Center

“This heartfelt collection of poems is an endless pursuit of what we hope to become.”

– Multicultural Review

As a Cuban-American, questions of Where do I belong? and What is Home? had always been at the center of my being and my poetry. But after relocating to Hartford in 1999 to teach at Central Connecticut State University, and also traveling for the first time through Europe and South America, those questions became even more complex and bewildering. They began to haunt me, whether sitting in a Roman piazza at dawn or walking through Venice past midnight; staring into the mouth of a volcano in Guatemala or into the eyes of lamb heads at a market in Barcelona; whether driving through the Brazilian countryside or down a causeway in Miami; visiting an aunt in Cuba or an old friend in Vermont; whether listening to a neighbor in Hartford playing Bach, or sitting quietly in my room watching the dust fall. These moments became the poems in this collection. They journal my journey both inward and outward into the world, questioning the idea of home in the foreign and the familiar, in the old and the new, through memories and hopes of what was yet to be.

Richard explores the familiar, unsettling journey for home and connections, those anxious musings about other lives: “Should I live here? Could I live here?” Whether the exotic (“I’m struck with Maltese fever …I dream of buying a little Maltese farm…) or merely different (“Today, home is a cottage with morning in the yawn of an open window…”), he examines the restlessness that threatens from merely staying put, the fear of too many places and too little time. The words are redolent with his Cuban heritage: Marina making mole sauce; Tía Ida bitter over the revolution, missing the sisters who fled to Miami; his father, especially, “his hair once as black as the black of his oxfords…” Yet this is a volume for all who have longed for enveloping arms and words, and for that sanctuary called home. “So much of my life spent like this-suspended, moving toward unknown places and names or returning to those I know, corresponding with the paradox of crossing, being nowhere yet here.” Blanco embraces juxtaposition. There is the Cuban Blanco, the American Richard, the engineer by day, the poet by heart, the rhythms of Spanish, the percussion of English, the first-world professional, the immigrant, the gay man, the straight world. There is the ennui behind the question: why cannot I not just live where I live? Too, there is the precious, fleeting relief when he can write”…I am, for a moment, not afraid of being no more than what I hear and see, no more than this:…” It is what we all hope for, too.

Read Excerpts

We’re Not Going to Malta

because the winds are too strong, our Captain announces, his voice like an oracle coming through the loudspeakers of every lounge and hall, as if the ship itself were speaking. We’re not going to Malta–an enchanting island country fifty miles from Sicily, according to the brochure of the tour we’re not taking. But what if we did go to Malta? What if, as we are escorted on foot through the walled “Silent City” of Mdina, the walls begin speaking to me; and after we stop a few minutes to admire the impressive architecture, I feel Malta could be the place for me. What if, as we stroll the bastions to admire the panoramic harbor and stunning countryside, I dream of buying a little Maltese farm, raising Maltese horses in the green Maltese hills. What if, after we see the cathedral in Mosta saved by a miracle, I believe that Malta itself is a miracle; and before I’m transported back to the pier with a complimentary beverage, I’m struck with Malta fever, discover I am very Maltese indeed, and decide I must return to Malta, learn to speak Maltese with an English (or Spanish) accent, work as a Maltese professor of English at the University of Malta, and teach a course on The Maltese Falcon. Or, what if when we stop at a factory to shop for famous Malteseware, I discover that making Maltese crosses is my true passion. Yes, I’d get a Maltese cat and a Maltese dog, make Maltese friends, drink Malted milk, join the Knights of Malta, and be happy for the rest of my Maltesian life. But we’re not going to Malta. Malta is drifting past us, or we are drifting past it–an amorphous hump of green and brown bobbing in the portholes with the horizon as the ship heaves over whitecaps wisping into rainbows for a moment, then dissolving back into the sea.

Somewhere to Paris

The sole cause of a man’s unhappiness is that

he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.

—Pascal, Pensées

The vias of Italy turn to memory with each turn

and clack of the train’s wheels, with every stitch

of track we leave behind, the duomos return again

to my imagination, already imagining Paris—

a fantasy of lights and marble that may end

when the train stops at Gare de l’Est and I step

into the daylight. In this space between cities,

between the dreamed and the dreaming, there is

no map—no legend, no ancient street names

or arrows to follow, no red dot assuring me:

you are here—and no place else. If I don’t know

where I am, then I am only these heartbeats,

my breaths, the mountains rising and falling

like a wave scrolling across the train’s window.

I am alone with the moon on its path, staring

like a blank page, shear and white as the snow

on the peaks echoing back its light. I am this

solitude, never more beautiful, the arc of space

I travel through for a few hours, touching

nothing and keeping nothing, with nothing

to deny the night, the dark pines pointing

to the stars, this life, always moving and still.

Papá’s Bridge

I am often asked about my dual life as an engineer and poet. In part, this poem is a response to that question. But equally so, here I was interested in exploring the connection, or “bridge” between landscape, memory, and emotion. We are three-dimensional beings. Our experiences always happen in the context of a specific physical landscape. To remember some one, some thing, or some emotion, often means to remember that some place to which these are connected.

Morning, driving west again, away from the sun

rising in the slit of the rearview mirror, as I climb

on slabs of concrete and steel bent into a bridge

arcing with all its parabolic y-squared splendor.

I rise to meet the shimmering faces of buildings

above treetops meshed into a calico of greens,

forgetting the river below runs, insists on running

and scouring the earth, moving it grain by grain.

And for a few inclined seconds every morning

I am twelve years old with my father standing

at the tenth-floor window of his hospital room,

gazing at this same bridge like a mammoth bone

aching with the gravity of its own dense weight.

The glass dosed by a tepid light reviving the city

as I watched and read his sleeping, wondering

if he could even dream in such dreamless white:

Was he falling? Was he flying? Who was he, who

was I underneath his eyes, flitting like the birds

across the rooftops and early stars wasting away,

the rush-hour cars pushing through the avenues

like the tiny blood cells through his vein, the I.V.

spiraling down like a string of clear licorice feeding

his forearm, bruised pearl and lavender, colors

of the morning haze and the pills on his tongue.

The stitches healed, while the room kept sterile

with the usual silence between us. For three days

I served him water or juice in wilting paper cups,

flipped through muted soap operas and game shows,

and filled out the menu cards stamped Bland Diet.

For three nights I wedged flat and strange pillows

around his bed, his body shaped like a fallen S

and mortared in place by layers of stiff percale.

When he was ordered to walk, I took his hand,

together we stepped to the window and he spoke

—You’ll know how to build bridges like that someday—

today, I cross this city, this bridge, still spanning

the silent distance between us with the memory

of a father and son holding hands, secretly in love.

Mexican Almuerzo in New England

Word is praise for Marina, up past 3:00 a.m. the night before her flight, preparing and packing the platos tradicionales she’s now heating up in the oven while the tortillas steam like full moons on the stovetop. Dish by dish she tries to recreate Mexico in her son’s New England kitchen, taste-testing el mole from the pot, stirring everything: el chorizo-con-papas, el picadillo, el guacamole. The spirals of her stirs match the spirals in her eyes, the scented steam coils around her like incense, suffusing the air with her folklore. She loves Alfredo, as she loves all her sons, as she loves all things: seashells, cacti, plumes, artichokes. Her hand waves us to circle around the kitchen island, where she demonstrates how to fold tacos for the gringo guests, explaining what is hot and what is not, trying to describe tastes with English words she cannot savor. As we eat, she apologizes: not as good as at home, pero bueno. . . It is the best she can do in this strange kitchen which Sele has tried to disguise with papel picado banners of colored tissue paper displaying our names in piñata pink, maíz yellow, and Guadalupe green–strung across the lintels of the patio filled with talk of an early spring and do you remembers that leave an after-taste even the flan and café negro don’t cleanse. Marina has finished. She sleeps in the guest room while Alfredo’s paintings confess in the living room, while the papier-mâché skeletons giggle on the shelves, and shadows lean on the porch with rain about to fall. Tomorrow our names will be taken down and Marina will leave with her empty clay pots, feeling as she feels all things: velvet, branches, honey, stones. Feeling what we all feel: home is a forgotten recipe, a spice we can find nowhere, a taste we can never reproduce, exactly.

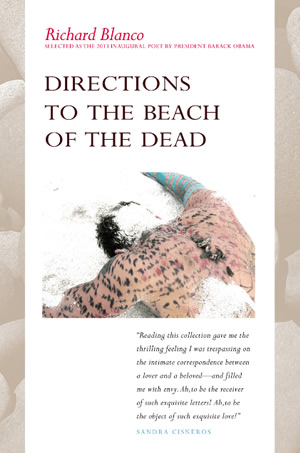

Praise & Reviews

“The universe of Richard Blanco is a place of lush, exhilarating landscapes and kindred souls. Its sweep is both magnificent and intimate in detail. And it shines most gloriously in his latest offering, Directions to The Beach of the Dead. His words are honey from Ochún herself.

– Liz Balmaseda, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer

“Richard Blanco has written a strong and beautiful book that takes his fine poetry forward to a new and exciting level. While these poems possess a keen sense of past and place, they move beyond nostalgia to the rich difficulties of the nowhere but here that is his clear milieu.

– Elizabeth Alexander, Yale University (Inaugural Poet President Obama 2009)

“For those of us who became devotees of Richard Blanco’s first, prize winning book, City of a Hundred Fires, for its luscious, eloquent voice, this second volume is reason for celebration. Mr. Blanco’s Directions to The Beach of the Dead is absolutely breathtaking and gorgeous in its quest for place, family, self-discovery. This book is as fresh as it is invigorating. Mr. Blanco’s voice is unmistakably brilliant and original. For all poetry lovers, this will be a difficult book to top

– Virgil Suarez, author of 90 Miles: Selected and New and Palm Crows

“In his new volume of poems, Richard Blanco extends his reach and strengthens his grasp. Part travel diary and part journal intime, Directions to The Beach of the Dead takes Blanco into uncharted territory, emotionally as well as geographically, showcasing his great gift for the precise notation of sights, thoughts, and feelings. This book confirms Blanco’s place as a strong and distinctive voice in American poetry.

– Gustavo Pérez Firmat, Columbia University

“Reading this collection gave me the thrilling feeling I was trespassing on the intimate correspondence between a lover and a beloved — and filled me with envy. Ah, to be the receiver of such exquisite letters! Ah, to be the object of such exquisite love!

– Sandra Cisneros, author of Caramelo, The House on Mango Street, and the poetry collection Loose Woman

“This work is about ‘the paradox of crossing, being nowhere yet here,’ where travelers, family members, and lovers seem perpetually in a state of ‘almost touching,’ of ‘learn[ing] to adore [their] losses.’ Heartfelt and elegant, these exquisitely crafted poems place Blanco in that pantheon of poetas from the Americas who have flourished in the Old World and the New. Directions to The Beach of the Dead — spanning three continents — marks Richard Blanco as arguably the most cosmopolitan poet of his generation.

– Francisco Aragón, author of Puerta del Sol

“In Directions to The Beach of the Dead, Richard Blanco enacts the exile’s great conflict in his astonishing, unerring poems of distance and desire, refuge and release. At once pensive and restless, full of both abandonment and abandon, this book is ultimately a journey to the haunted, utterly familiar places in our own hearts. Lost Cuba, newfound love, immemorial time — this soulful poet gives us all that is at once impossible to have ever owned, and yet ever within

the reach of our having known.

– Rafael Campos, author of Landscape with Human Figure

“Richard Blanco is a troubadour of Exile. . .with aching stories of its displacement, loss and nostalgia, — that uniquely Cuban reverie — for what might have been.

– Ann Louise Bardach, author of Cuba Confidential: Love and Vengeance in Miami and Havana

“This heartfelt collection of poems is an endless pursuit of what we hope to become. Takes the reader on a splendid journey through time, love, family, and heritage.”

– Multicultural Review