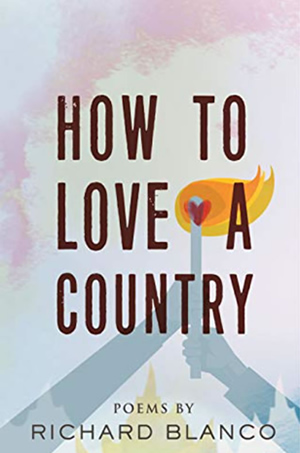

A new collection from the renowned inaugural poet exploring immigration, gun violence, racism, LGBTQ issues, and more, in accessible and emotive verses. Richard Blanco digs deep into the very marrow of our nation through poems that interrogate our past and present, grieve our injustices, and note our flaws, but also remember to celebrate our ideals and cling to our hopes.

As presidential inaugural poet, memoirist, public speaker, educator, and advocate, Richard Blanco has crisscrossed the nation inviting communities to connect to the heart of human experience and our shared identity as a country. In this new collection of poems, his first in over seven years, Blanco continues to invite a conversation with all Americans. Through an oracular yet intimate and accessible voice, he addresses the complexities and contradictions of our nationhood and the unresolved sociopolitical matters that affect us all.

The poems form a mosaic of seemingly varied topics: the Pulse Nightclub massacre; an unexpected encounter on a visit to Cuba; the forced exile of 8,500 Navajos in 1868; a lynching in Alabama; the arrival of a young Chinese woman at Angel Island in 1938; the incarceration of a gifted writer; and the poet’s abiding love for his partner, who he is finally allowed to wed as a gay man. But despite each poem’s unique concern or occasion, all are fundamentally struggling with the overwhelming question of how to love this country.

Seeking answers, Blanco digs deep into the very marrow of our nation through poems that interrogate our past and present, grieve our injustices, and note our flaws, but also remember to celebrate our ideals and cling to our hopes. In the landmark poem “American Wandersong,” which forms the center of the book, the poet reveals himself to readers in a disarming and kinetic sequence of stanzas, striving to find his place amid the physical and emotional landscapes of our country.

Through this groundbreaking volume, Blanco unravels the very fabric of the American narrative and pursues a resolution to the inherent contradiction of our nation’s psyche and mandate: e pluribus unum (out of many, one). Charged with the utopian idea that no single narrative is more important than another, this book asserts that America could and ought someday to be a country where all narratives converge into one, a country we can all be proud to love and where we can all truly thrive.

Read Excerpts

Complaint of El Río Grande

for Aylin Barbieri

I was meant for all things to meet:

to make the clouds pause in the mirror

of my waters, to be home to fallen rain

that finds its way to me, to turn eons

of loveless rock into lovesick pebbles

and carry them as humble gifts back

to the sea which brings life back to me.

I felt the sun flare, praised each star

flocked about the moon long before

you did. I’ve breathed air you’ll never

breathe, listened to songbirds before

you could speak their names, before

you dug your oars in me, before you

created the gods that created you.

Then countries—your invention—maps

jigsawing the world into colored shapes

caged in bold lines to say: you’re here,

not there, you’re this, not that, to say:

yellow isn’t red, red isn’t black, black is

not white, to say: mine, not ours, to say

war, and believe life’s worth is relative.

You named me big river, drew me—blue,

thick to divide, to say: spic and Yankee,

to say: wetback and gringo. You split me

in two—half of me us, the rest them. But

I wasn’t meant to drown children, hear

mothers’ cries, never meant to be your

geography: a line, a border, a murderer.

I was meant for all things to meet:

the mirrored clouds and sun’s tingle,

birdsongs and the quiet moon, the wind

and its dust, the rush of mountain rain—

and us. Blood that runs in you is water

flowing in me, both life, the truth we

know we know: be one in one another.

Declaration of Interdependence

Such has been the patient sufferance…

We’re a mother’s bread, instant potatoes, milk at a checkout line. We’re her three children pleading for bubble gum and their father. We’re the three minutes she steals to page through a tabloid, needing to believe even stars’ lives are as joyful and bruised.

Our repeated petitions have been answered only by repeated injury…

We’re her second job serving an executive absorbed in his Wall Street Journal at a sidewalk café shadowed by skyscrapers. We’re the shadows of the fortune he won and the family he lost. We’re his loss and the lost. We’re a father in a coal town who can’t mine a life anymore because too much and too little has happened, for too long.

A history of repeated injuries and usurpations…

We’re the grit of his main street’s blacked-out windows and graffitied truths. We’re a street in another town lined with royal palms, at home with a Peace Corps couple who collect African art. We’re their dinner-party talk of wines, wielded picket signs, and burned draft cards. We’re what they know: it’s time to do more than read the New York Times, buy fair-trade coffee and organic corn.

In every stage of these oppressions we have petitioned for redress…

We’re the farmer who grew the corn, who plows into his couch as worn as his back by the end of the day. We’re his TV set blaring news having everything and nothing to do with the field dust in his eyes or his son nested in the ache of his arms. We’re his son. We’re a black teenager who drove too fast or too slow, talked too much or too little, moved too quickly, but not quick enough. We’re the blast of the bullet leaving the gun. We’re the guilt and the grief of the cop who wished he hadn’t shot.

We mutually pledge to each other our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor…

We’re the dead, we’re the living amid the flicker of vigil candlelight. We’re in a dim cell with an inmate reading Dostoevsky. We’re his crime, his sentence, his amends, we’re the mending of ourselves and others. We’re a Buddhist serving soup at a shelter alongside a stockbroker. We’re each other’s shelter and hope: a widow’s fifty cents in a collection plate and a golfer’s ten-thousand-dollar pledge for a cure.

We hold these truths to be self-evident…

We’re the cure for hatred caused by despair. We’re the good morning of a bus driver who remembers our name, the tattooed man who gives up his seat on the subway. We’re every door held open with a smile when we look into each other’s eyes the way we behold the moon. We’re the moon. We’re the promise of one people, one breath declaring to one another: I see you. I need you. I am you.

Mother Country

To love a country as if you’ve lost one: 1968,

my mother leaves Cuba for America, a scene

I imagine as if standing in her place—one foot

inside a plane destined for a country she knew

only as a name, a color on a map, or glossy photos

from drugstore magazines, her other foot anchored

to the platform of her patria, her hand clutched

around one suitcase, taking only what she needs

most: hand-colored photographs of her family,

her wedding veil, the doorknob of her house,

a jar of dirt from her backyard, goodbye letters

she won’t open for years. The sorrowful drone

of engines, one last, deep breath of familiar air

she’ll take with her, one last glimpse at all

she’d ever known: the palm trees wave goodbye

as she steps onto the plane, the mountains shrink

from her eyes as she lifts off into another life.

To love a country as if you’ve lost one: I hear her

—once upon a time—reading picture books

over my shoulder at bedtime, both of us learning

English, sounding out words as strange as the talking

animals and fair-haired princesses in their pages.

I taste her first attempts at macaroni-n-cheese

(but with chorizo and peppers), and her shame

over Thanksgiving turkeys always dry, but countered

by her perfect pork pernil and garlic yuca. I smell

the rain of those mornings huddled as one under

one umbrella waiting for the bus to her ten-hour days

at the cash register. At night, the zzz-zzz of her sewing

her own blouses, quinceañera dresses for her grown nieces

still in Cuba, guessing at their sizes, and the gowns

she’d sell to neighbors to save for a rusty white sedan—

no hubcaps, no air-conditioning, sweating all the way

through our first vacation to Florida theme parks.

To love a country as if you’ve lost one: as if

it were you on a plane departing from America

forever, clouds closing like curtains on your country,

the last scene in which you’re a madman scribbling

the names of your favorite flowers, trees, and birds

you’d never see again, your address and phone number

you’d never use again, the color of your father’s eyes,

your mother’s hair, terrified you could forget these.

To love a country as if I was my mother last spring

hobbling, insisting I help her climb all the way up

to the US Capitol, as if she were here before you today

instead of me, explaining her tears, cheeks pink

as the cherry blossoms coloring the air that day when

she stopped, turned to me, and said: You know, mijo,

it isn’t where you’re born that matters, it’s where

you choose to die—that’s your country.

My Father in English

First half of his life lived in Spanish: the long syntax

of las montañas that lined his village, the rhyme

of sol with his soul—a Cuban alma—that swayed

with las palmas, the sharp rhythm of his machete

cutting through caña, the syllables of his canarios

that sung into la brisa of the island home he left

to spell out the second half of his life in English—

the vernacular of New York City sleet, neon, glass—

and the brick factory where he learned to polish

steel twelve hours a day. Enough to save enough

to buy a used Spanish-English dictionary he kept

bedside like a bible—studied fifteen new words

after his prayers each night, then practiced them

on us the next day: Buenos días, indeed, my family.

Indeed más coffee. Have a good day today, indeed—

and again in the evening: Gracias to my bella wife,

indeed, for dinner. Hiciste tu homework, indeed?

La vida is indeed difícil. Indeed did indeed become

his favorite word which, like the rest of his new life,

he never quite grasped: overused and misused often

to my embarrassment. Yet the word I most learned

to love and know him through: indeed, the exile who

tried to master the language he chose to master him,

indeed, the husband who refused to say I love you

in English to my mother, the man who died without

true translation. Indeed, meaning: in fact/en efecto,

meaning: in reality/de hecho, meaning to say now

what I always meant to tell him in both languages:

thank you/gracias for surrendering the past tense

of your life so that I might conjugate myself here

in the present of this country, in truth/así es, indeed.

published in The New Yorker, February 2019

Dreaming a Wall

are redder, bluer, whiter than theirs, believes

his bees work harder, his soil richer, blacker.

He hears birds sing sweeter in his trees, taller

and fuller, too, but not enough to screen out

the nameless faces next door that he calls

liars, thieves who’d steal his juicier fruit, kill

for his wetter rain and brighter sun. He keeps

a steely eye on them, mocks the too cheery

colors of their homes, too small and too close

to his own, painted white, with room to spare.

He curses the giggles of their children always

barefoot in the yard, chasing their yappy dogs.

He wishes them dead. Closes his blinds. Refuses

to let light from their windows pollute his eyes

with their lives. Denies their silhouettes dining

at the kitchen table, laughing in the living room,

the goodnight kisses through every bedroom.

Slouched in his couch, grumbling over the news

he dismisses as fake, he changes the channel

to an old cowboy western. Amid the clamor

of gunshots he dozes off thinking of his dream

where he stakes a line between him and all

his neighbors, stabs the ground as he would

their chests. Forms a footing cast in blood-red

earth, bends steel bars as he would their bones

with his bare fists and buries them in concrete.

Mortar mixed thick with anger, each brick laid

heavy with revenge, he smiles as he finishes

the last course high enough to imagine them

more miserable and lonely than him alone

behind his wall, worshiping his greener lawn,

praising his fresher air, under his bluer, bluer sky.

Watch Video

Until We Could, Video Poem

Praise & Reviews

“This clear-seeing and forthright volume marks Blanco as a major, deeply relevant poet.”

– Booklist, Starred Review ★

“Generous and deeply felt, the long prose poems in this moving new collection from presidential inaugural poet Blanco (after Looking for the Gulf Motel) help us understand what it means to cross a border . . . . Submit to the fierce pleasure of Blanco’s art.”

– Library Journal

“Blanco’s contributions to the fields of poetry and the arts have already paved a path forward for future generations of writers . . . Our Nation was built on the freedom of expression, and poetry has long played an important role in telling the story of our Union and illuminating the experiences that unite all people.

– President Barack Obama

“From a country courting implosion, a country at odds with its own brutal and breathless backstory, a country with a name that sparks both expletive and prayer, rises Richard Blanco’s muscular, resolute voice—sounding stanzas of the confounded heart and clenched fist, of indignation and insurrection. This is an urgent gathering of sweet, fractured, insistent American noise—the stories that feed us and the stories we’d rather forget—re-teaching us all the right ways there are to love a country that so often forgets how to love us back.

– Patricia Smith, author of Incendiary Art

“At a time when we are once again debating our identity as Americans, this splendid collection of poems from a great storytelling poet is an absolute treasure that speaks to the things that hold us together despite the things that split us apart.

– Doris Kearns Goodwin, author of Leadership in Turbulent Times

“In these times of hate, we need poets who speak of love. Richard Blanco’s new collection is a visionary hymn of love to the human beings who comprise what we call this country. Whether he speaks in the voice of an immigrant who came here long ago, or the very river an immigrant crosses to come here today, Blanco sings and sings. This, the song says, is the way out—for all of us.

– Martín Espada, author of Vivas to Those Who Have Failed

“A frank and wonderful collection that calls America a work in progress, that describes the poet himself as a grade school bully who loved the other boy he hit and one could readily cry with him now, everything is alive here in his book: the Rio Grande as sentient and knowing, all this with a jazz musician’s timing. Richard Blanco writes about the elusive poundingness of love.

– Eileen Myles, author of Evolution

“This new collection is vibrant, tragic, exhilarating, deeply in love with people and their stories and heartbreakingly engaged with our struggling nation. These are poems for every season, for large and small moments and very much for our time.

– Amy Bloom, author of White Houses

“Richard Blanco has risen to the challenge of writing poetry that serves our nation. This is both a responsibility and an honor. I am moved, proud, overjoyed, and inspired.

– Sandra Cisneros, author of The House on Mango Street

“Powerful, personal, and full of life, these poems delve into the complex intricacies of what it means to call the United States home. A masterful poet who is clear-eyed and full of heart, Blanco explores the country’s haunted past while offering a bright hope for the future.

– Ada Limón, author of Bright Dead Things

“In this timely collection, Richard Blanco masterfully embraces his role as a civic poet, confronting our nation’s riddled history in the light of conscience. At once personal and political, these lyric narratives decry injustice and proclaim our hopes.

– Carolyn Forché, author of The Country Between Us

“There is a uniting oneness to these passionate and remarkable poems, each finely wrought line a bridge from one heart to another, a love song of this burdened earth and all its flawed inhabitants. Richard Blanco is this century’s Walt Whitman.

– Andre Dubus III, author of Gone So Long